Dec. 4, 1968: Patentability of computer programs legally recognized in Prater and Wei

A tumultuous series of court hearings granted a software patent to two engineers and helped establish the legality of software patents.

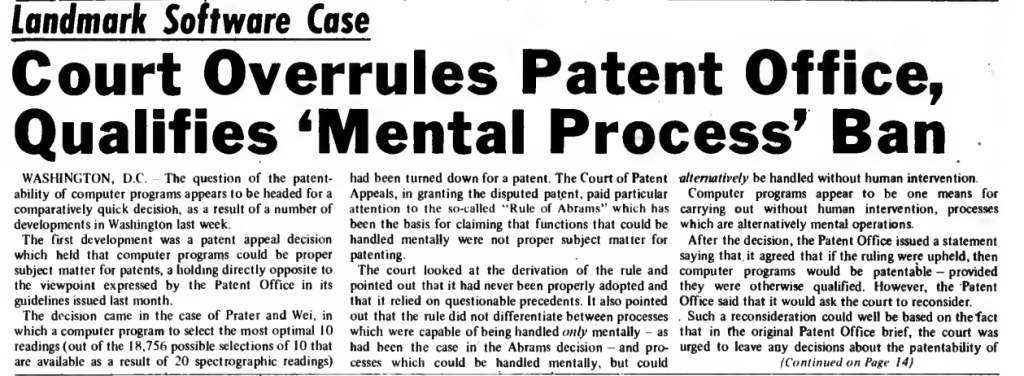

History was made in June of 1968 when the world’s first software patent was granted to researcher Martin Goetz. However, the legality of software patents was far from settled. A series of landmark rulings from the US Court of Customs and Patent Appeals in late 1968 and early 1969 were critical both in granting a patent to engineers Charles Prater and James Wei and in challenging the existing guidelines against software patents.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has strict guidelines as to what constitutes patentable subject matter, with “process” being one acceptable type and the classification under which software best fits. However, processes that are considered “abstract concepts” (such as mathematics) or “mental processes” are excluded from being considered proper patentable subject matter. Before Prater and Wei’s patent, the Patent Office excluded software from being patented, since many computer programs were a series of mathematical steps and could, in theory, be carried out in the human mind.

Onto the scene stepped Prater and Wei, engineers at oil company Mobil, with a patent application for a computer program that could select the optimal 10 spectrographic readings from a set of over 180,000 possible combinations. The patent described methods that could be carried out either by computer or by doing linear algebra by hand. Their patent was initially rejected due to the “Rule of Abrams,” which stated that a process is unpatentable if the novel steps proposed in the process existed in the “mental steps.”

In November of 1968, the US Court of Customs and Patent Appeals (CCPA) ruled to grant Prater and Wei the disputed patent. In their ruling, they made the key observation that software processes – clearly capable of being handled without human thought – do not fall under the Rule of Abrams just because they could be carried out by mental steps. The Patent Office challenged the patent ruling, resulting in a rehearing in March of 1969. The rehearing ruled in favor of Prater and Wei again, but used a different argument, stating that the Rule of Abrams did not apply to Prater and Wei because they had included an apparatus (a computer) for implementing their process without human intervention. This ruling superseded the first, essentially granting Prater and Wei a patent for a specialized computer rather than a software process.

The CCPA rulings changed the Patent Office guidelines, making it much easier for software patent applications to receive consideration. However, it wasn’t until a subsequent CCPA case granting a patent to geophysicist Albert Musgrave that the court established a “technological arts” standard for patentability, effectively reaffirming the original CCPA ruling that software processes do not fall under the mental steps doctrine. Since these rulings, software patents have increased year after year, today generating billions in revenue annually.

–By Kathleen Esfahany